The concept of karma is one of the most profound and comprehensive philosophy. Far from being a simple notion of cause and effect, karma represents a sophisticated understanding of how our actions shape not only our current life but countless lives to come. The ancient scriptures, or Shastras, provide detailed classifications of karma that help us understand the mechanics of this cosmic law.

The Three Primary Types of Karma

1. Sanchita Karma: The Accumulated Storehouse

Sanchita karma represents the vast reservoir of all karmic impressions accumulated across innumerable lifetimes. This is the complete inventory of every action, thought, and word from our soul’s entire journey through existence.

Sanchita karma is too vast to be experienced in a single lifetime; only a part of it becomes active in each birth.

The Yoga Vasishtha describes this concept beautifully: “As a man gathers fruits in the harvest season and stores them for use at a later time, so does the soul accumulate the fruits of its actions through countless births.”

The Brihadaranyaka Upanishad (4.4.5) states: “According to his karma, according to his knowledge, he attains various states.” This verse acknowledges the accumulation of karmic seeds that determine our future experiences.

Think of Sanchita karma as an enormous warehouse containing seeds of countless varieties; some will sprout into flowers, others into thorns. Not all of these seeds will germinate in a single lifetime; they wait in storage until conditions are ripe for their manifestation, or think of it as a massive cosmic hard drive storing every file of your soul’s journey.

2. Prarabdha Karma: The Portion Set in Motion

Prarabdha karma is the specific portion of Sanchita karma that has been selected to fructify in the current lifetime. This determines the fundamental framework of our present existence, our body, family, location of birth, major life events, and the general trajectory of our life.

The Shvetashvatara Upanishad (5.12) explains: “Those who are born are born in accordance with their karma and grow according to their karma.”

The Bhagavad Gita (13.21) illuminates this further: “Purusha (the soul) experiences the qualities born of Prakriti (nature) because of association with it. Attachment to these qualities is the cause of its birth in good and evil wombs.”

Prarabdha karma is often compared to an arrow that has already left the bow; it must complete its trajectory. This is why certain aspects of life seem predetermined or unavoidable. However, this doesn’t mean we are helpless; while we cannot change the arrow’s path, we can change how we respond to where it lands.

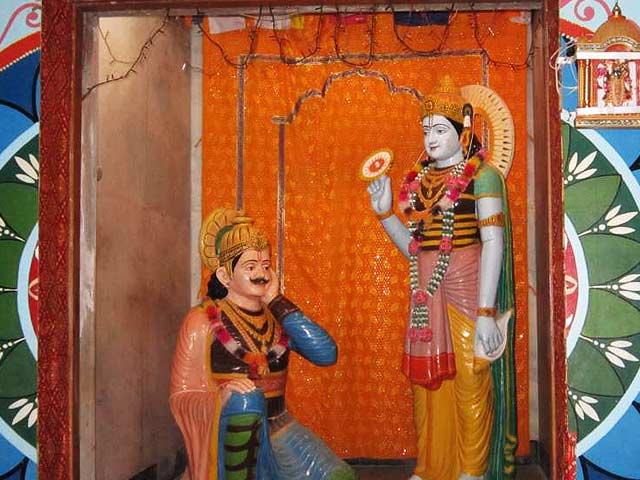

The story from the Mahabharata illustrates this: Even Bhagwan Krishna could not prevent the curse that would end the Yadava dynasty, despite being the Supreme Lord himself, because that was their Prarabdha karma coming to fruition.

3. Kriyamana (Agami) Karma: The Present Actions

Kriyamana karma, also known as Agami karma, refers to the new karma we are creating at this moment through our current actions, thoughts, and intentions. This is the domain of free will and conscious choice.

Your choices today become your destiny tomorrow.

Kriyamana karma flows back into the Sanchita pool and shapes future experiences and births.

This is where transformation is possible. Right decisions, attitude, and awareness can alter the course of your destiny.

The Bhagavad Gita (2.47) famously declares: “You have a right to perform your prescribed duties, but you are not entitled to the fruits of your actions. Never consider yourself to be the cause of the results of your activities, nor be attached to inaction.”

The Manusmriti (12.3) states: “Action, which springs from the mind, from speech, and from the body, produces either good or evil results; by action are caused the (various) conditions of men, the highest, the middling, and the lowest.”

This is where human agency becomes most evident. Every moment presents an opportunity to plant seeds that will shape our future, whether in this life or lives to come. The quality of our intentions, the nature of our choices, and the discipline of our actions all contribute to the karmic account we’re building.

The Question of Free Will and Limitations:

While Kriyamana karma represents the domain of free will, the scriptures acknowledge that this freedom is not absolute; it operates within certain constraints:

1. Prarabdha as the Framework: Our current actions occur within the circumstances created by Prarabdha karma. We cannot choose our birth, initial family, body type, or fundamental life situations, but we can choose how we respond to them.

The Brihadaranyaka Upanishad (4.4.5) states: “Now as a man is like this or like that, according as he acts and according as he behaves, so will he be.” This suggests action within given conditions.

2. The Three Gunas (Qualities of Nature): Our free will is influenced by the three gunas, sattva (purity), rajas (activity), and tamas (inertia), which condition our mind and tendencies.

The Bhagavad Gita (14.5) explains: “Material nature consists of three modes, goodness, passion, and ignorance. When the eternal living entity comes in contact with nature, O mighty-armed Arjuna, he becomes conditioned by these modes.”

The Bhagavad Gita (3.5) further clarifies: “Everyone is forced to act helplessly according to the qualities he has acquired from the modes of material nature; therefore no one can refrain from doing something, not even for a moment.”

3. Samskaras (Mental Impressions): Past karmic impressions create deep-rooted tendencies that influence our choices. Breaking free from these patterns requires conscious effort and spiritual practice.

The Yoga Sutras (4.9) notes: “Because memory and samskaras are the same in form, there is an unbroken continuity in the fruition of karma, even though separated by class, location, and time.”

4. Limited Knowledge: We act with incomplete information about consequences, which restricts truly free choice. The Bhagavad Gita (5.15) states: “The Supreme Lord does not assume anyone’s sinful or pious activities. Embodied beings, however, are bewildered because of the ignorance which covers their real knowledge.”

The Freedom Within Bondage:

We have real but limited free will. The Kathopanishad (2.2.15) describes the human situation: “Having realized the Self, which is soundless, intangible, formless, undecaying, and likewise tasteless, eternal and odorless; having realized That which is without beginning and end, beyond the Great, and unchanging, one is freed from the jaws of death.”

The key insight is that while our free will in Kriyamana karma is constrained by:

- Past karma (Prarabdha and Sanchita)

- Our inherent nature (gunas and samskaras)

- Our level of knowledge and consciousness

- External circumstances

We still possess genuine agency to:

- Choose our response to circumstances

- Purify our mind through spiritual practice

- Gradually transcend limiting patterns

- Move from ignorance toward knowledge

- Act with increasing detachment and wisdom

The Bhagavad Gita (18.63) honors this limited but real freedom: “Thus I have explained to you knowledge still more confidential. Deliberate on this fully, and then do what you wish to do.”

Progressive Liberation:

As one progresses spiritually, the scope of free will actually expands. Through yoga, meditation, and self-knowledge, one can:

- Burn past samskaras (Yoga Sutras 4.30)

- Transcend the influence of the gunas (Bhagavad Gita 14.20)

- Act from wisdom rather than conditioning

Ultimately, the Bhagavad Gita (2.48) teaches: “Perform your duty equipoised, O Arjuna, abandoning all attachment to success or failure. Such equanimity is called yoga.”

The goal is not unlimited free will within samsara, but liberation (moksha) from the entire karmic mechanism, a state where the enlightened being acts spontaneously from wisdom without creating binding karma.

Additional Classifications

Krit, Karit, Anumodit, and Saha Karma: The Degrees of Participation

The scriptures recognize that karma is not only created through direct action but also through various levels of involvement and complicity. This classification appears in texts like the Manusmriti and Yoga scriptures, highlighting the subtle ways we accumulate karmic consequences.

Krit Karma (Directly Performed Action): Karma created by actions we personally execute with our own hands, speech, or mind. This is the most obvious form of karmic accumulation.

The Manusmriti (12.3) states: “Action, which springs from the mind, from speech, and from the body, produces either good or evil results.” This emphasizes that Krit karma encompasses all three instruments of action.

When we ourselves commit an act, whether righteous or unrighteous, we bear the full karmic consequence. If you plant a tree with your own hands, you earn the merit. If you harm someone directly, you bear that karmic debt.

Karit Karma (Causing Others to Act): Karma accumulated by instigating, ordering, or compelling others to perform actions on our behalf. The person who commands the action shares in the karmic result along with the executor.

The Manusmriti (4.169) warns: “He who instigates another to do an evil deed, he who assists in its commission, and he who does it himself, all three are equally culpable.”

The Mahabharata provides numerous examples of this principle. When Duryodhana ordered the disrobing of Draupadi, though Dushasana physically committed the act, Duryodhana bore equal, if not greater, karmic responsibility for instigating it.

This principle reminds us that delegating harmful actions doesn’t absolve us of responsibility. A king who orders unjust executions, an employer who commands unethical practices, or anyone who uses their authority to cause others to act wrongly accumulates Karit karma.

Anumodit Karma (Approved or Consented Action): Karma accrued through approval, encouragement, or silent consent to actions performed by others. Even without direct involvement, our agreement or tacit support creates karmic bonds.

The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali (2.34) addresses this: “Vitarka (negative thoughts) such as violence etc., whether committed, caused to be committed, or approved, whether arising from greed, anger or delusion, whether slight, medium or intense, result in endless pain and ignorance. This is why one must cultivate the opposite.”

The Bhagavad Gita (3.21) also implies this principle: “Whatever action a great man performs, common men follow. And whatever standards he sets by exemplary acts, all the world pursues.” Those who approve and follow bear karmic consequences for their consent.

When we cheer for injustice, applaud wrongdoing, or remain silent when we should speak against evil, we accumulate Anumodit karma. Conversely, when we celebrate virtue and encourage righteousness, we earn positive karma even without direct action.

This is perhaps the most subtle yet pervasive form of karma in modern society—the karma of being a bystander, a silent witness, or an approving audience to both good and evil.

Saha Karma (Collaborative or Collective Action): Karma created through joint participation, where multiple individuals work together toward a common goal. All participants share in the collective karmic result proportionate to their involvement and intention.

The Bhagavad Gita (3.25) illustrates collective action: “As the ignorant perform their duties with attachment to results, the learned may similarly act, but without attachment, for the sake of leading people on the right path.”

The Mahabharata extensively demonstrates Saha karma in the war at Kurukshetra. Every soldier, charioteer, and strategist on both sides accumulated karma based on their participation in the collective action, though their individual karmic accounts varied based on their intentions and roles.

The Rig Veda (10.191.2) celebrates righteous collective action: “May we move in harmony; may we speak in harmony; may our minds be in agreement. United be your purpose, united be your hearts.”

This principle operates in families, communities, organizations, and nations. When a community builds a temple, all contributors share the merit. When a corporation engages in harmful practices, all knowing participants share the karmic burden. When a nation goes to war, the collective karma is distributed among all who supported, participated in, or benefited from that action.

Practical Implications:

Understanding these four categories transforms how we view responsibility:

- Personal Accountability: We cannot escape karmic consequences by having others do our dirty work (Karit karma).

- The Power of Approval: Our consent, applause, or silence matters morally and karmically (Anumodit karma).

- Collective Responsibility: We share in the karma of groups we belong to and support (Saha karma).

- Complete Mindfulness: We must be conscious not only of what we do (Krit karma) but also what we cause, approve, and collectively participate in.

The Manusmriti (11.55) summarizes this comprehensive understanding: “By mental sin one becomes a bird, by verbal sin an animal, and by bodily sin an immovable object.” The text recognizes that karma operates at multiple levels through various forms of participation.

Karma, Vikarma, and Akarma: The Nature of Action

The Bhagavad Gita offers a sophisticated understanding of three types of action based on their spiritual quality:

Karma (Righteous Action): Actions performed in harmony with dharma (righteous duty) and scriptural guidance. The Bhagavad Gita (3.8) advises: “Perform your prescribed duty, for doing so is better than not working. One cannot even maintain one’s physical body without work.”

Vikarma (Prohibited Action): Actions that violate dharmic principles and scriptural injunctions. The Bhagavad Gita (16.23) warns: “He who discards scriptural injunctions and acts according to his own whims attains neither perfection, nor happiness, nor the supreme destination.”

Akarma (Non-binding Action): The most subtle and liberating category, actions that create no karmic bondage. The Bhagavad Gita (4.18) reveals this profound secret: “One who sees inaction in action, and action in inaction, is intelligent among men, and he is in the transcendental position, although engaged in all sorts of activities.”

The Bhagavad Gita (4.20) further describes the enlightened sage: “Having abandoned attachment to the fruits of action, ever satisfied and independent, he performs no karmic action, though engaged in all kinds of activities.”

This concept of Akarma represents the pinnacle of spiritual wisdom, performing actions with complete detachment, offering them as service to the Divine, thereby transcending the karmic cycle entirely.

Sakama and Nishkama Karma: The Question of Desire

This classification focuses on the motivation behind our actions:

Sakama Karma (Desire-motivated Action): Actions performed with attachment to results and expectation of rewards. The Bhagavad Gita (2.43) describes those attached to desires: “Men of small knowledge are very much attached to the flowery words of the Vedas, which recommend various fruitive activities for elevation to heavenly planets, resultant good birth, power, and so forth.”

Nishkama Karma (Desireless Action): Actions performed as selfless duty without attachment to outcomes; this is the essence of Karma Yoga. The Bhagavad Gita (3.19) proclaims: “Therefore, without being attached to the fruits of activities, one should act as a matter of duty, for by working without attachment one attains the Supreme.”

The Bhagavad Gita (5.10) beautifully describes this state: “One who performs his duty without attachment, surrendering the results unto the Supreme Lord, is unaffected by sinful action, as the lotus leaf is untouched by water.”

The Ishopanishad (verse 2) echoes this wisdom: “One may aspire to live a hundred years by working selflessly.” (न कर्म लिप्यते)

The Path to Liberation

Understanding these different types of karma is not merely an intellectual exercise; it’s a practical guide to spiritual liberation (moksha). The scriptures reveal that while Prarabdha karma must be experienced, and Sanchita karma lies dormant, we have complete control over our Kriyamana karma.

The Mundaka Upanishad (3.1.3) offers hope: “When the seer sees the self-effulgent Creator, the Lord, the Purusha, the progenitor of Brahma, then he, the wise one, shakes off good and evil, becomes stainless, and reaches the supreme unity.”

By cultivating Nishkama karma and striving for Akarma through devotion and wisdom, we can burn the seeds of accumulated karma and eventually transcend the cycle of birth and death (samsara).

The Bhagavad Gita (4.37) provides this powerful promise: “As a blazing fire turns firewood to ashes, O Arjuna, so does the fire of knowledge burn to ashes all karma.”

How do we apply this wisdom practically?

- Accept Prarabdha with Equanimity: Understand that certain aspects of life are results of past actions. Face them with courage and grace rather than resistance.

- Exercise Conscious Choice in Kriyamana: Be mindful of your current actions, thoughts, and words. Remember that you are constantly creating your future.

- Cultivate Nishkama Karma: Practice performing your duties without obsessive attachment to results. Do your best and surrender the outcome.

- Seek Akarma through Spiritual Practice: Engage in actions as offerings to the Divine. Let meditation, selfless service, and devotion transform ordinary actions into spiritual practice.

- Study and Reflect on Scripture: Regular engagement with texts like the Bhagavad Gita provides ongoing guidance and inspiration.

The karma is neither fatalistic nor purely mechanistic. It represents a sophisticated understanding of how past, present, and future interweave, while always leaving room for human agency, wisdom, and grace.

As the Bhagavad Gita (18.66) ultimately reveals: “Abandon all varieties of dharmas and simply surrender unto Me alone. I shall liberate you from all sinful reactions; do not fear.”

The path through karma leads ultimately beyond karma, to a state of pure being, consciousness, and bliss where the soul recognizes its eternal nature and unites with the Supreme. This is the promise held within the profound wisdom of the Shastras, waiting for each seeker to discover and realize in their own journey.